What Does 10-4 Mean? Why Police And Truckers Say It On The Radio

In 1977, a little movie called "Smokey and the Bandit" burst on the scene that not only made a star out of Pontiac's Trans Am, but made liberal use of truck driver slang and the 10-Codes they use to communicate via citizens band (CB) radio. The following year (1978), another film called "Convoy," starring Kris Kristofferson and Ali MacGraw, doubled down on all that crazy lingo.

It was based on a crossover chart-topping #1 song from 1976 of the same name by country music singer C.W. McCall and helped popularize the saying, "10-4, good buddy" — a shortened way to acknowledge that a message was received; think of it as an easier way to quickly and easily communicate the sentiment "affirmative" or "OK." Thanks to the film and music industries, CB radios became so popular that millions of people snatched up their own long-distance communication devices by the end of the decade. Remember, this was a time when cell phones had yet to become mainstream.

Today, the use of 10-Code is prevalent in the many police procedurals that flood television and streaming services, not to mention their use in the plethora of military movies and video game series like "Call of Duty" and "Battlefield." But the history of 10-Codes goes back roughly a century, long before people were coming up with clever handles to use (like Rubber Duck and Pig Pen) and saying things like "breaker, breaker 1-9" and "10-4, good buddy."

Get off my radio channel!

It might seem to many denizens of our modern society, where streaming devices are now the norm, that radios are an old-timey contraption only found in our cars or what our grandparents listen to baseball games on. The first radio was invented in 1896 by Guglielmo Marconi, but they weren't used in a public safety capacity until the Detroit Police Department first used them in 1928.

While this revolutionary new tool replaced the stationary locked "Call Booths" equipped with a telegraph machine, they were still few and far between and only allowed for one-way communication between police headquarters and the patrol officer. In order to respond, the officer had to track down a telephone or call booth. Even when that technology evolved, early radios only had a single channel that everyone shared. Two-way radios were introduced in the Bayonne, New Jersey Police Department in 1933. However, as departments grew, the radio traffic clogging these limited channels became unbearable, especially with multiple officers trying to talk simultaneously.

The creation of 10-codes came about due to necessity. Police departments needed to find a way to keep the channel as free from traffic and cross-talk as possible. In a June 1935 issue of the Association of Police Communications Officers (APCO) Bulletin, a suggestion was made to create a set of "brevity codes" based on procedure symbols used by the U.S. Navy. Initially, they weren't standardized, but they allowed departments and officers to communicate quickly and thus free up the channel.

The APCO Ten Signals for police use

Charles "Charlie" Hopper, the communications director for the Illinois State Police, is credited with developing the APCO Ten Signals in 1937. Another facet of radios at the time was their need to "charge up" before sending a message. The word "ten" was a short one-syllable word and could be said and understood easily. Each code starts with the number ten, followed by a second number that means something specific. Examples include:

- 10-0: Use Caution

- 10-4: Acknowledgement (OK)

- 10-10 Negative

- 10-40: Fight in Progress

- 10-100: Dead Body Found

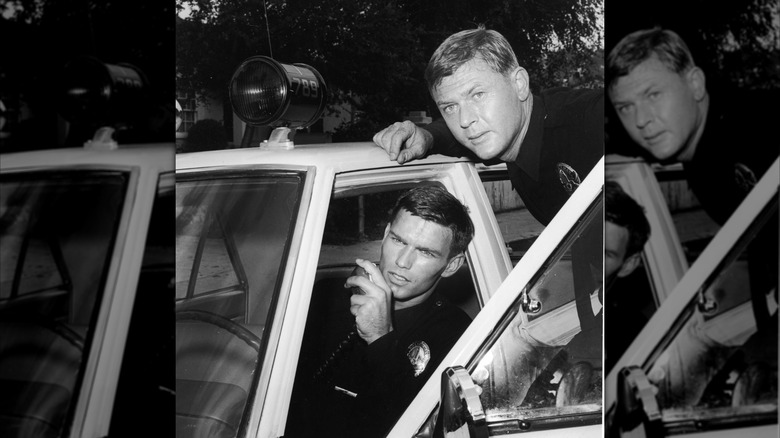

Despite the need and apparent success of 10-Codes, it still took until 1955 for a somewhat standardized version to be used among various police departments. Ironically, this was also the year a show called "Highway Patrol" hit television and, for the first time, introduced these police codes to the general population. When "Adam-12" aired in 1968, it showed that California used penal codes — 187 for murder, 459 for burglary, 415 for disturbance, or 211 for robbery.

At first, these "secret" codes also kept criminals from knowing what the police were saying. Over the years, though, departments created localized codes to maintain those secrets and thus strayed from any form of standardization. States, not to mention cities, had all manner of criminal violations and bizarre driving laws that used different codes. Since then, their ubiquitous and prolific use in all types of media has mostly revealed all those "secrets."

Truckers needed help during the OPEC oil embargo in 1973

Although CB radios have been around since 1945, truckers really didn't start using them en masse until the OPEC oil embargo hit in 1973. Gas prices skyrocketed, and stations quickly ran out of gas (and diesel). Truckers quickly found that they needed to track down what stations were still open so they could fuel up and stay on the road to get paid. They also ran into similar radio congestion and adopted the 10-code used by police departments, but with some colorful additions, like:

- Bear meant policeman.

- Super skate was code for "sports car."

- Chicken coop signaled a weigh station.

- Evil Knievel was a motorcycle cop.

- Choke and puke meant restaurant.

Localized police codes clashed in January 1982 when Washington's busiest airport, highway, and subway line were all forced to close at the same time thanks to a terrible set of wholly unrelated events. Nineteen responding agencies, each with their own codes, caused unparalleled communication difficulties. These issues cropped up again during the terrorist attacks on 9/11 and again when Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005.

In 2006, the U.S. government recommended that 10-codes be eliminated and police departments should instead use plain language, something many fire departments and emergency medical services (EMS) have since already done. Despite the suggestion, some departments still use them, citing safety and security concerns even though they're no longer a "secret" to anyone, especially with the widespread public use of readily available police scanners. That's a big 10-4, good buddy.